Including hypermobility due to Ehlers Danlos Syndrome, Marfan Syndrome, & Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders

Hypermobility is classified as having one or more joints with a higher-than-normal range of motion. There are multiple disorders that are attributed to hypermobility including Ehlers Danlos Syndrome (EDS), Marfan Syndrome (MF), and Joint Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders (JHS). If you’re interested in learning more about these and how they are related to joint hypermobility, click here.

Prevalence of Hypermobility:

While these disorders have been considered quite rare, there may be more prevalence than previously expected. One study published in BMJ Journal found that 194.2 of 100,000, or about 10 in 5,000, cases of EDS or JHS were found in 2016/2017 (1). This is significantly more than the estimate in 2002 of 1 case in 5,000 (2). MS is also estimated at 1 case in 5,000 according to the CDC (3). More research is needed to clarify the true prevalence of EDS and JHS. As we learn more, I believe it is important for those who have hypermobility or have a partner, child, or client with hypermobility to have resources of how to manage the stability issues that are present as a result of Hypermobility.

Value of stability, strength, and posture for those with hypermobility:

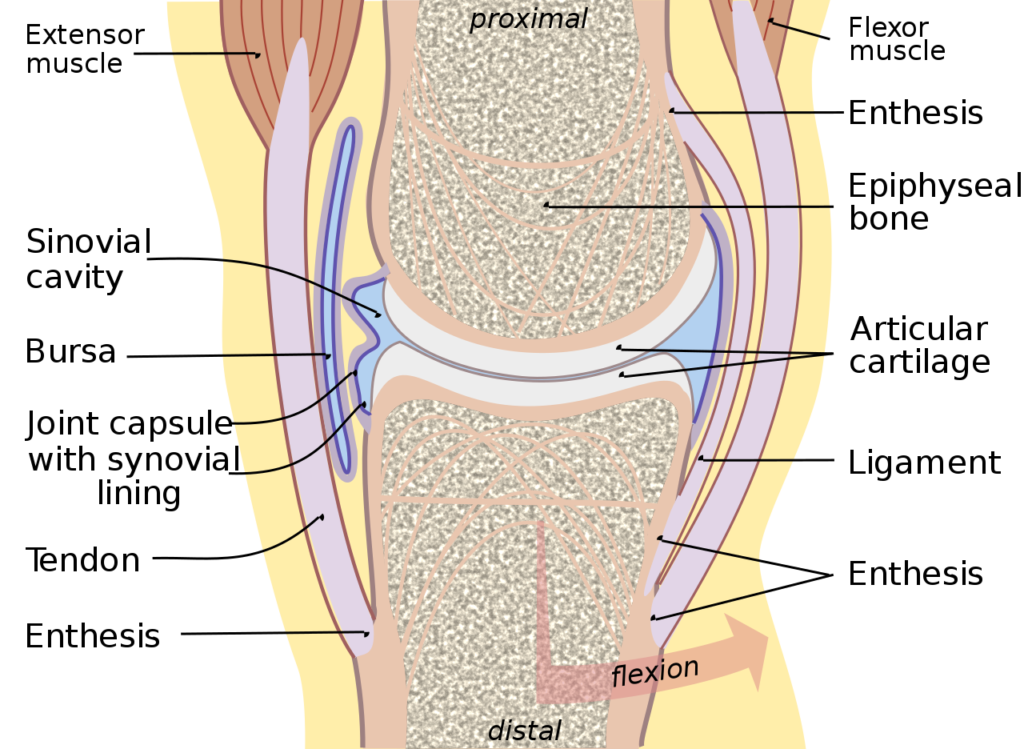

While a larger than normal range of motion (ROM) can look cool, issues often occur due to the lack of stability in one or multiple joints. One way to think about this phenomenon is to visualize a joint and the extremes of mobility in that joint. For example, below is a diagram of a knee.

Imagine this joint with limited ROM, extremely tight tendons, ligaments, and muscles would allow very little movement. It is protected from impact AND able to hold weight due to its lack of movement.

On the other end….

Imagine this joint with UNLIMITED ROM. Either bone can slip to the side, compress, or expand with ease. It has a high amount of flexibility but, it lacks the structural stability needed to hold a lot of weight or protect from impact.

Most people sit somewhere in the middle of these extremes, and certain athletic events require a specific range. For example:

- Martial arts are commonly known to contain both flexibility AND strength, strengthening and stabilizing joints while also increasing flexibility.

- Heavy weightlifters are commonly stiffer, and a certain amount of stiff-ness is required to be able to maintain the joint structure while under a heavy load.

As mentioned above, impact can be highly detrimental with hypermobility due to little resistance, leading to partial or full joint dislocations, torn ligaments, or tendons, etc. This can occur from impact from something like a car accident or a smaller impact like tripping and rolling ankle. When this occurs repeatedly joint inflammation, joint pain, and muscle stiffness around the joint will commonly happen. In order to decease overall inflammation, it is important to stabilize by building strength.

Effects of Current Fitness Culture on Hypermobile Individuals

The cultural norms of Strength and Fitness are always changing and vary by locations. However, there are some common approaches and practices that are often not helpful for those with hypermobility. Some examples include:

- Encouragement to push past pain and discomfort to do more

- The prevalence of high impact, high intensity workouts. Examples include: HIIT, jumping, sprinting, As many reps possible (AMRAP), etc.

- The lack of awareness or attention to balanced posture AND movement patterns

- Focus on heavy weights straight away without enough time or technique centered practice. A push to go heavier as soon as possible in order to “work harder”.

- Utilizing compound movements without enough technique practice. For example, going straight into doing pushups without first learning how to engage the shoulders in a hand plank.

While I am not saying that these practices are inherently bad, I do think that despite good intentions they can cause negative effects, specifically on the hypermobile population.

For hypermobile individuals I have worked with, these practices can lead to chronic pain and dislocations, and are not generally an effective method to gain strength. This is a particular challenge as people who are hypermobility both need to gain strength to support their joints, but frequently cannot practice standard strength building, weightlifting, or exercise programs without high risk of injury.

Pitfalls:

Outside of cultural norms, there are some specific practices that are often pitfalls of strength training with hypermobility, they include:

- Too much too fast. This can include weight, reps, or movement difficulty

- High intensity: Working at a higher heart rate or perceived rate of exertion. This often leads to low awareness of movement AND body sensation.

- High impact: Jumping, running, etc. Note: High impact exercises are possible with hypermobility, but require adequate background or buildup of strength first

- Not enough focus on postural alignment: Focusing on moving fast or moving more weight often decreases focus on posture and positioning during the movement

- Too little rest: This includes both during and apart from your workouts. Recovery, both between a set of movements AND after your completed workout, is particularly important with hypermobility.

A Principle based approach:

As we have discussed, due to the increase in instability for those with hypermobility, improving stability, strength, and alignment (posture) are particularly important and helpful for those with Hypermobility.

Below I have outline principles to be utilized in strength and conditioning goals. I have found these principles are often helpful for those suffering from chronic joint pain for other reasons other than hypermobility. These principles can be used to adapt your current workout and strength routine or build a new one.

The goal of these principles is to have lasting results and decrease risk of injury with strength and fitness.

Let’s take a look…

- Working towards long term progress with daily adaptations: Every day is a bit different. To decrease injury risk, it is important to adjust to daily ups and downs. Adjusting individual exercises or the overall routine is helpful to be able to WORKOUT the following day, allowing for sustainable training and true change. An example would look like, decreasing the number of squat sets due to fatigue, pain, or other reasons.

- Mental focus: Maintaining form requires significant focus and energy. Focus levels will vary day to day and thus it is important to be aware of your current focus and adjust for this aspect of training. For example, if focus is low try an activity that is easier or safer. When focus is high, incorporate more challenging movements. This does take some practice to learn what is best on high and low focus days.

- Practice strength but focus on stability and engagement: There are many ways to train strength and conditioning. Due to the importance of stability for those who are hypermobile, incorporating stability incrementally can be very helpful. Examples include incorporating single leg balance strength, half kneeling positions, moving planks, dumbbell work, etc. Note: It is important to incorporate stability work SLOWLY. Adding in too much stability work too quickly can lead to injury and/or imbalanced movement patterns. It can be helpful to work with a professional to complete these movements safely.

- Prioritize Postural Alignment: Balanced neutral posture takes effort to both find and stabilize, particularly for those with hypermobility. Focusing on alignment is helpful as it keeps the spine and joints in the correct patterns and positioning, which in turn helps to decrease risk of injury in joints. For example, it is more important to do a squat with neutral spinal position and less weight then to add weight and compromise positioning. As this compromise is likely to result in pain and/or injury.

- Slow and steady: When exercising it can be easy to get caught up in the individual workout, to get excited and add weight, reps, or difficulty. It is helpful to remember that consistency is the goal. You are most likely to gain strength if you continue to strength train. Meaning, if you push too hard today and risk injury, you may not be able to train tomorrow. Going slow and steady may feel boring, but it is much more effective to build long term sustainable strength.

- First. Isometric Second. Eccentric and Third. Concentric: When learning a new movement, I suggest trying it in this order. This allow you to learn to stabilize and be in balanced posture with less injury risk. Below I have listed each for a push up, but the concept can apply to any movement. Isometric: Static. Ex. Hand plank Eccentric: Lengthening a muscle, also known as doing a negative. Ex. Lowering from a hand plank to the ground, the negative of a push up. Concentric: Shortening a muscle. Ex. Push up from the ground.

The challenge with principles is also what makes them functional in my opinion. They allow you to take the overall principle and apply them to your goals, training protocol, practices, and more. Allowing you the freedom to discover places that you can make small changes that will help to decrease risk of injury, inflammation, joint pain, dislocations, etc.

I hope you enjoyed reading this, feel free to contact me here if you would like to chat more or have any questions.

References: